Image by Technology Networks, Immunology and Microbiology

iGEM Project 2023 | Part 4

We have mentioned the debate that is still taking place regarding the inclusion of bacteriophages, and more generally viruses, among the “living things”. The reason for the discussion is simple, these organisms depend on a host cell for their replication: a virus cannot replicate itself and more generally it cannot do anything except infect new cells, but it does it perfectly. After entering the cell, a virus manages to take total control of it and in a few minutes millions of copies of the virus have been produced, so many that the host cell literally explodes.

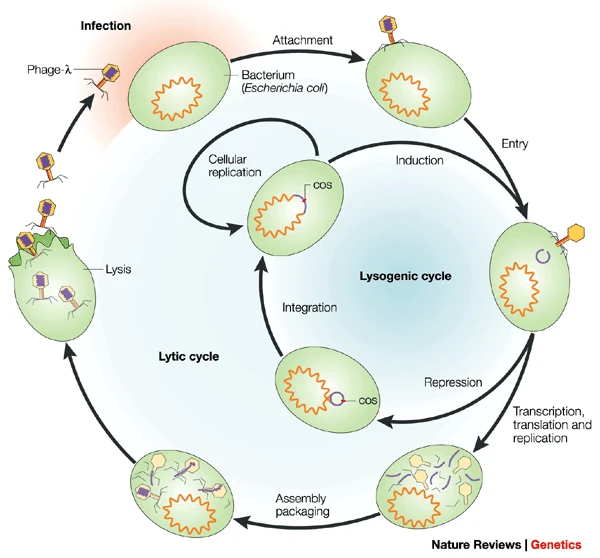

Image by Nature Reviews Genetics, The future of bacteriophage biology

While for animal and plant viruses the cycle of infection is complex and varies from species to species, for bacteriophages we can encounter two alternative mechanisms which are called lytic cycle and lysogenic cycle. The first, simpler and more direct consists of what I described a moment ago: the phage enters the cell, takes control over the cellular machinery so it synthesize phage proteins, those of the capsid, and duplicating the viral genome to produce new particles named virions. These viruses accumulate inside the cell until it explodes, it is said to lyse, causing its death and at the same time the release of new virions.

The lysogenic cycle is more complex (there is always one easy thing and a difficult one), but its study has been crucial for understanding some basic molecular mechanisms of bacterial cells. In fact, in this case, once the virus enters the cell, it does not take control of it, but if the right conditions are established, it integrates its genome into the bacterial one, i.e. it inserts its DNA into the bacteria chromosome. Here the information is stored, silently, even for generations of cells, until the conditions change and, thanks to some specific signals, the phage genome is excised, cut from the bacterial one, transcribed and translated so the lytic cycle begins. Currently, in many bacterial genomes we find traces of viral DNA that have remained stably integrated, due to imprecise cuts and other more complex phenomena.